“The dissolution of the black family may do more harm to black mobility than any other single factor.”

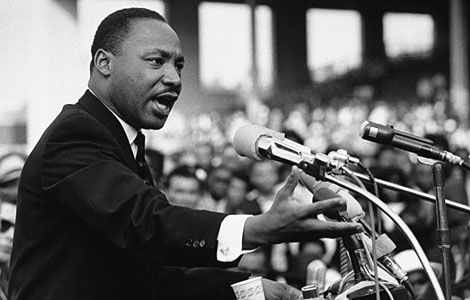

This is the conclusion of The Economist, surveying the changes that have happened in the 50 years since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I have a dream speech.” Perhaps the most famous words of a speech in the twentieth century come from Dr. King’s dream, that “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

The Great Issue of Our Time

In an age when virtually everything is overstated and polarized, identifying this dream as ‘the great issue of our time’ sounds like yet another hyperbolic, politicized polemic. However, it is not an overstatement. The reason that this phrase is possibly the most quoted phrase of the most famous speech of the last century is because it tersely and eloquently captured an essential element of human flourishing. The fact that this grand dream remains unrealized testifies to its monumental importance. The conclusion of The Economist and others that family is the most powerful limiting factor on black flourishing only further confirms this.

The Preeminence of Character

Dr. King’s dream was not a dream of meritocracy, where children are judged on the basis of their skills or achievements. Rather, he dreamed of a society that valued virtue above skin color, and above skill. Dr. King was a living embodiment of that dream – the persistent, courageous pursuit of love and justice in a world disfigured by hatred and injustice. He knew well that this vision and this life could not take root except in a society in which character is the proper measure of a person.

The Character Crisis

Character is in crisis in two important and interrelated ways. First, the content of virtue is now significantly disputed. There are many visions of ‘the good’ and many versions of ‘virtue.’ If children ought to be judged by the content of their character, what is the standard by which we judge them? Is there one? Or is each free to choose his or her own good?

Second, the most powerful institution for the formation of character is in disarray. In 1965,Patrick Daniel Moynihan, a Democratic senator from New York, published “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action” because he was alarmed at the rate of unwed births among African Americans – and recognized it as critical for the health and prosperity of that community. It was, at that time, 23%. As of the 2010 census, the unwed birth rate now stands at 40.8% of births for all ethnic groups and 72.5% for African Americans. The institution most central to the formation of character has crumbled. The institution that can (and often still does) provide the most safe, stable, and loving environment for children to mature in life-long learning and healthy relationships in increasingly unsafe and unstable.

The Role of Family

Parents play the crucial and defining role in character formation, and they do so disproportionately in the earliest years of a child’s life. They communicate norms by establishing the rules of the home. They set expectations of what is normal by their daily actions and interactions. Children learn to see themselves, and to relate to other people, to their environment, and to their Creator from their parents (or those who act in their stead). Parents’ choices affect every aspect of a child’s life: where to live, what to eat, what to read, how to use media, how to resolve conflict, how (and when and where) to learn, and with whom to associate. Thoughtfully or carelessly, well or poorly, parents impart to their children a vision of “the good life” and a sense of what is good, true and beautiful. This is true of married parents, single parents, divorced parent, foster parents, adoptive parents and de facto parents.

Parents are the Key to Children’s Character

The civil rights movement of the 1960′s is an extraordinary case study in the power of parents to shape children’s character. Consider Dr. King himself. His home life shaped his posture to the world. His loves were molded and formed in the home. From his parents he learned – in practice, not just in theory – how to respond to the wicked hostility of his racist neighbors. From his father he learned to use the confessional language of Christian faith in public as the backbone of his work for justice. Dr. King’s remarkable character was formed in the family . . . even while they were a persecuted minority.

Or take Ruby Bridges, the daughter of a sharecropper in Louisiana, who was among the first black children “integrated” into a white school. Despite poverty, oppression and active persecution, she learned from her parents to love her enemies, to speak peace to them and even pray for them when they yelled death threats at her – a six year old child. Ruby’s family was the key to forming her character in the earliest years of life. Their faithful labor changed the history of our nation.

Difficulty, Disadvantage and Virtue

One of the reasons that we rightly celebrate and admire King, Bridges and others is because of the extraordinary difficulty they overcame to do good. If their fight had been an easy one, it would not be worthy of the history books. The difficulty of their good task is the index of its virtue.

Consider the difficulty facing parents today: a muddy picture of virtue, a vicious bombardment of false promises, and tumult in the institution of the family. That difficulty is the index of the beauty of courageously articulating a true vision of virtue, and then laboring faithfully to nurture virtue in children. For parents who lack a spouse, the fight is harder. For those who lack a supportive community it is harder still. For those who have never seen a healthy family, the difficulty compounds. Difficulty and disadvantage don’t make character formation impossible; they make the struggle for it more virtuous and more beautiful.

Fulfilling the Dream: Upholding Character, and Loving Parents

If we share Dr. King’s dream, we must recover his spine in publicly articulating and embodying a positive vision of virtue, and we must show courage and perseverance in loving parents of young children by equipping them to cultivate virtue in their children . . . or our dream will be nothing more than wishful thinking.

How can you live the dream?

Where have you seen parents showing this sort of courage? Where have you seen others supporting parents in their work? Where have you had glimpses of individuals and families valuing character above achievement or color?